- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Series: Andean Foods El Pallar

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

International academic cooperation between the Wiese Foundation and Universidad Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul ...

Clothing at El Brujo: footwear ...

To receive new news.

Por: Ismael Alva Ch. And Leslie Zúñiga Becerra

By José Ismael Alva Ch. And Leslie Zúñiga Becerra

“Eaten these green lilies, with their tender vanillas in oil and vinegar, they are given away; also keep them dry as beans, and the Spaniards and Indians eat them sometimes stewed and sometimes cooked with oil and vinegar, and in any case they are a good delicacy. "

Bernabé Cobo, 1653

The pallar (Phaseolus lunatus) is a legume native to America. It is one of the most popular ingredients in contemporary Peruvian cuisine and provides remarkable nutrients to our body. Join us to briefly know the history of the pallar, its preparations and benefits in the diet.

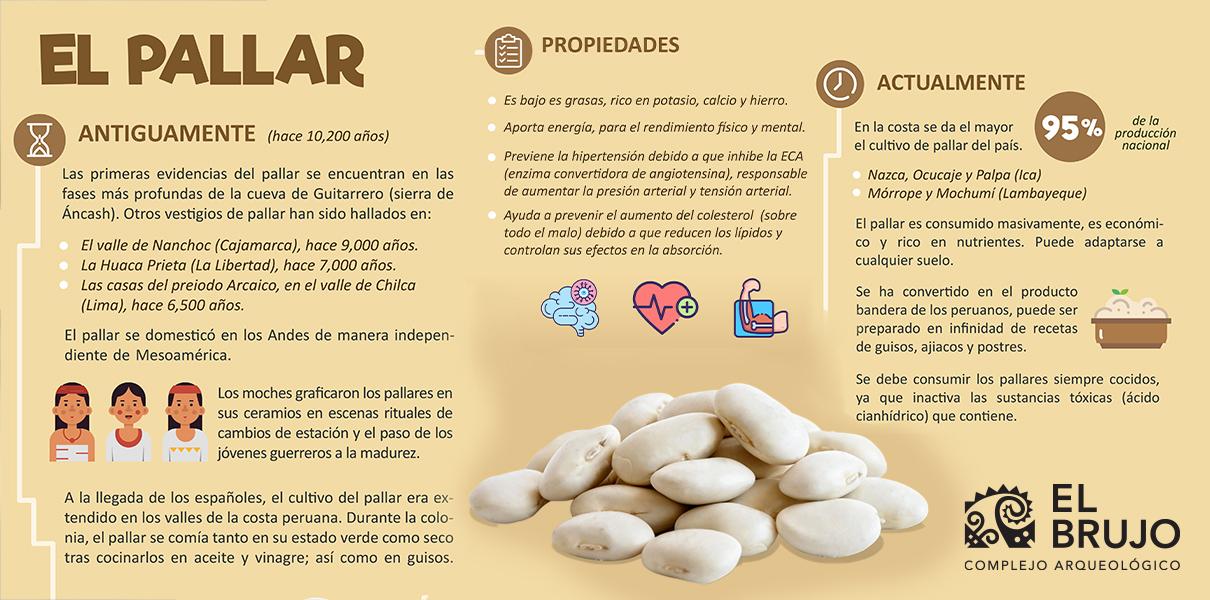

El pallar in the Prehispanic Andes

The oldest evidences of the pallar are found in the deepest phases of the Guitarrero cave, located in the Callejón de Huaylas (Sierra de Áncash), with dates ranging between 8,200 and 7,800 BC. In the Nanchoc Valley (Cajamarca Region) the remains associated with the consumption of this legume correspond to 7,000 BC. [1].

On the North Coast, the initial phase of the Huaca Prieta, located at the southern end of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex (La Libertad Region), contains pallar remains with dates of approximately 5,000 BC, a time in which the populations seasonally occupied the coastline and consumed these seeds together with avocados, squash, among other edible species [2, 3].

In the Central Coast, the pallar pods from the houses of the Archaic period in the Chilca valley have an antiquity that fluctuates between 4,700 and 4,400 BC. In Caral, Supe valley, the charred pallar seeds date back to 2,600 BC. [1].

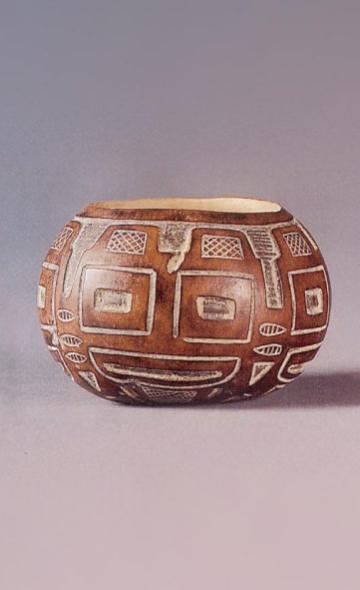

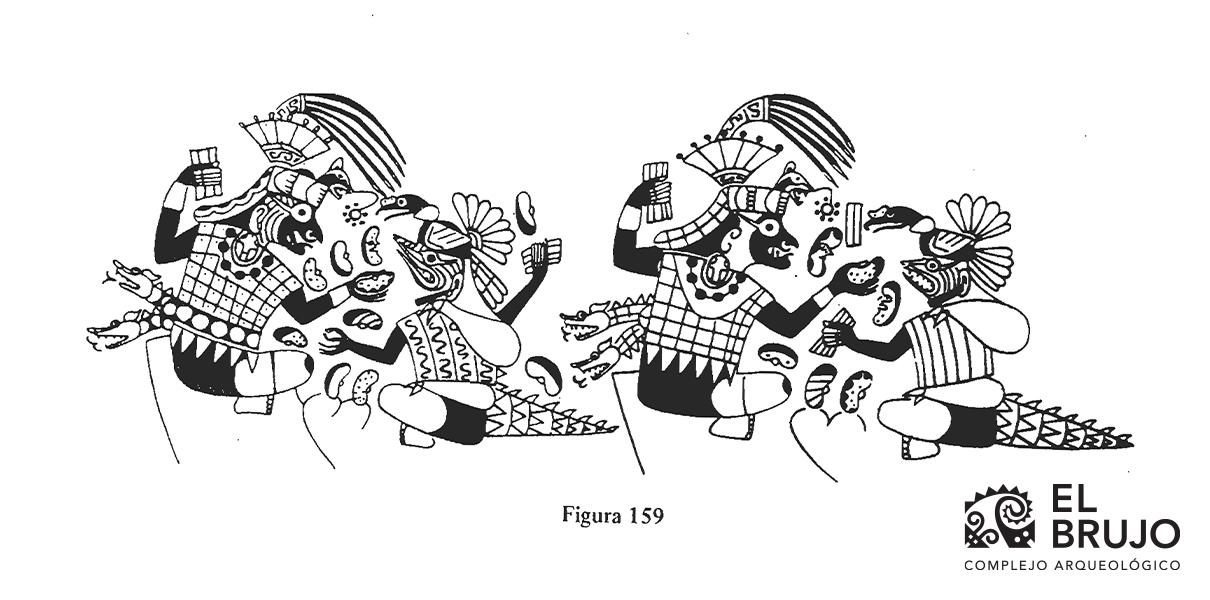

The Moches (100 - 800 AD) constantly drew pallares in their ceramics in a naturalistic way and at other times with anthropomorphic attributes. Representations of this seed appear in scenes related to the rituals of seasonal changes as part of the Andean agricultural calendars, as well as in the passage of young warriors to maturity, carried out as ceremonial battles [4, 5].

At the arrival of the Spaniards, the cultivation of the pallar was extended in the valleys of the Peruvian coast. The Hispanics settled in America incorporated this legume into their diet, because according to Father Bernabé Cobo, the pallar was eaten both in its green and dry state after cooking them in oil and vinegar; although they were also consumed in stews [6].

Pallar's Production in Contemporary Peru

Currently on the coast there is the largest pallar cultivation in the country. The Nazca, Ocucaje and Palpa areas, in the Ica region, and the Mórrope and Mochumí areas, in the Lambayeque region, concentrate a total of 95% of the national production of this legume [7].

A legume loved by the people

The pallar is consumed massively in the popular sectors of the cities, because it is cheap and rich in nutrients. It is a food that can adapt to any soil, especially those that have already begun to suffer the effects of global warming, as well as in areas with scarce water resources and desert soils.

It has become the flagship product of Peruvians. It is in all markets and can even be found in presentations such as canned pallar preserves. It can be prepared in countless recipes of stews, ajiacos and desserts that brighten up the Peruvian gastronomic culinary [8].

The lollipops should always be eaten cooked, as it inactivates the toxic substances (hydrocyanic acid) it contains. An adequate portion for a healthy person reaches 1 cooked cup of lollipops that can even be combined with cereals or tubers or with any source of animal protein. You can decrease the serving to half a cup if you need to lose weight [9].

Benefits of consuming lollipops

This legume provides energy, from its starches, excellent for physical and mental performance. Pregnant women and people who must keep their weight under control, such as athletes, can find in the pallar a rich way to obtain energy [9].

It prevents hypertension because it inhibits ACE (angiotensin converting enzyme), responsible for increasing blood pressure and blood pressure. Inhibitors significantly reduce the morbidity (number of sick patients in a given place and time) and mortality in patients with myocardial infarction or heart failure [10].

It helps prevent the increase in cholesterol (especially bad cholesterol) due to which the components of the seeds of this and other legumes reduce lipids and control their effects on the absorption of cholesterol in the intestine [11].

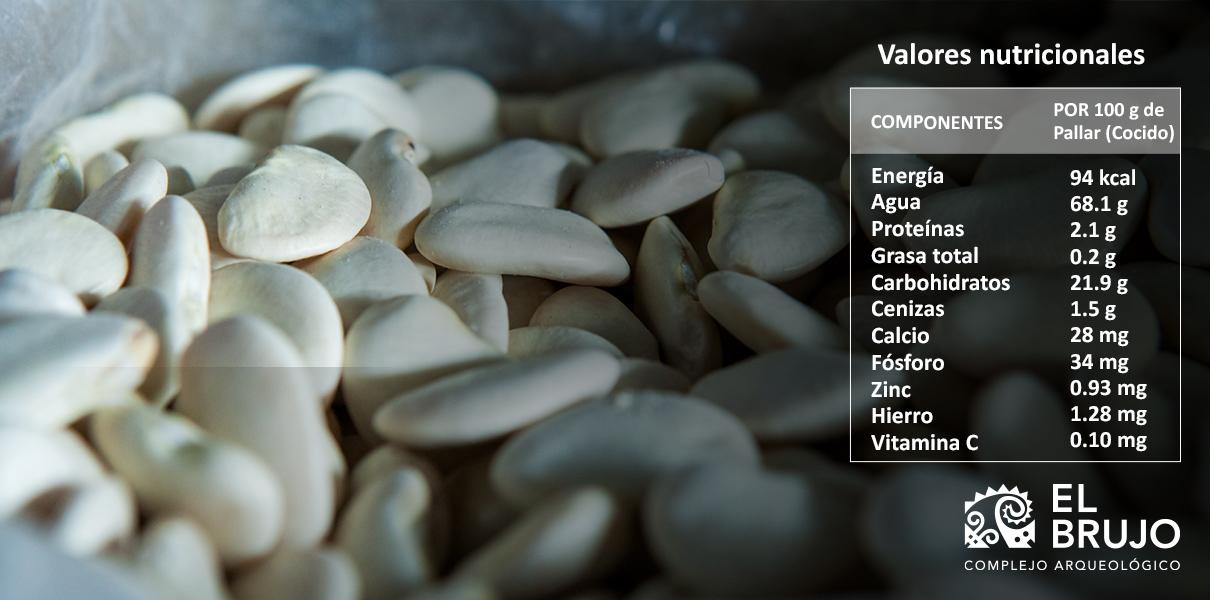

Nutritional value

Note. Adapted from "Peruvian food composition tables". Prepared by Reyes G., María; Goméz-

Sanchez P., Iván; Espinoza B., Cecilia. Copyright 2017 by Ministry of Health, National Institute of Health

Bibliography

[1] León, E. (2013). 14,000 años de alimentación en el Perú. Lima: Fondo Editorial Universidad de San Martín de Porres.

[2] Bonavia, D., V. Vásquez, T. Rosales, T, Dillehay, P. Netherly, P. y K. Benson. (2017). Plant Remains. Where the Land Meet the Sea. Fourteen Millennia of Human History at Huaca Prieta, Peru. T. Dillehay (Ed.), pp. 367-433. Austin: University of Texas.

[3] Dillehay, T. y D. Bonavia. (2017). Cultural Phases and Radiocarbon Chronology. Where the Land Meet the Sea. Fourteen Millennia of Human History at Huaca Prieta, Peru. T. Dillehay (Ed.), pp. 88-108. Austin: University of Texas.

[4] Hocquenghem, A-M. (1984). El hombre y el pallar en la iconografía moche. Anthropologica, II (2), 403-411.

[5] Hocquenghem, A-M. (1987). Iconografía Mochica. Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

[6] Cobo, B. (1964 [1653]). Historia del Nuevo Mundo. Primera parte. Biblioteca de Autores Españoles Tomo XCI. Madrid: Ediciones Atlas.

[7] Ministerio de Agricultura y Riego. (2016). Boletín Evolución de Producción y Precios de Legumbres. Mes de Julio.

[8] Velásquez, H. C. (2007). Alimentos incas para enfrentar el calentamiento global.

[9]Abbu S., S. [Siempre en casa RPP]. (18 de junio del 2015). Beneficios de comer pallares. [imagen adjunta] [Publicación de estado]. Facebook. https://web.facebook.com/SiempreEnCasaRPP/posts/856712681082541/?_rdc=1&_rdr

[10] Ruiz Ruiz, J. C., Segura Campos, M. R., Betancur Ancona, D. A., & Chel Guerrero, L. A. (2013). Encapsulation of Phaseolus lunatus protein hydrolysate with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory activity. ISRN biotechnology, 2013.

[11] Oboh, H. A., & Omofoma, C. O. (2008). The effects of heat treated lima beans (Phaseolus lunatus) on plasma lipids in hypercholesterolemic rats. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition, 7(5), 636-639.

[12] Reyes García, M., Gómez-Sánchez Prieto, I., & Espinoza Barrientos, C. (2017). Tablas peruanas de composición de alimentos.

Researchers , outstanding news